Individual Psychology

A “Living Force of Progress”

Alfred Adler delivered hundreds of public lectures. Many of these lecture halls were filled, and the topics of crime, schooling, as well as love and marriage, child education, were very popular. The themes of his lectures resulted in his 1931 book “What Life Should Mean to You.”

Während wir uns Gedanken über staatliche Unterstützungsmaßnahmen, den Wahlkampf und andere Themen machen, sollten wir nicht vergessen, dass eines unserer Hauptprobleme die Bildung unserer Kinder ist. Diese Kinder werden schon bald die Welt regieren. Wie gut sie das tun werden, hängt davon ab, wie gut ihre Köpfe in den Schulen gefördert werden.

Alfred Adler, 15. Juli 1936, The Minneapolis Star, S. 6

1926

First American lecture tour.

AVenues included Community Church of New York, The New School for Social Research, Harvard University, and Columbia University.

1928-30

Professorship at Columbia University

Adler takes up a professorship at Columbia University. He also gives lectures at the New School for Social Research in New York City and founds a Child Guidance Clinic (Institute for Educational Assistance).

1932-34

Professorship at Long Island College of Medicine (Brooklyn, NYC)

Adler takes up a professorship at the Long Island College of Medicine, founds the Adler Medical Psychology Clinic in Brooklyn, and continues his work at the New School for Social Research in Manhattan.

1935

Emigration to the United States

In view of the growing threats in Austria, Alfred and Raissa Adler emigrate to the United States and take up residence at the Gramercy Park Hotel. Their adult children — Alexandra (33), Kurt (30), and Nelly (25) — also follow them to the U.S.

Valentine is already living in the Soviet Union, where she dies under tragic circumstances in 1942.

Apr. 1935

Founding of the International Journal of Individual Psychology

From the International Journal of Individual Psychology evolved today’s Journal of Individual Psychology, which is published by the University of Texas Press.

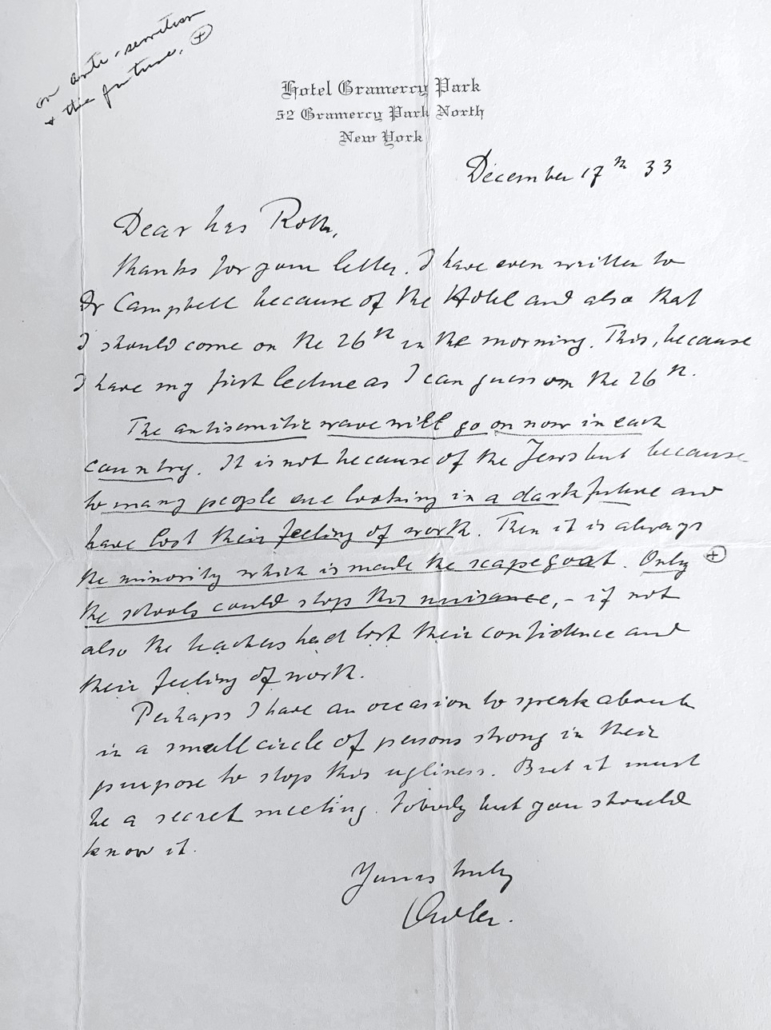

Concerns about the situation in Europe and the future of Europe. The original letter, donated by Evelyn’s niece, is in the archival collection of Adler University, Chicago, US.

Alfred Adler. Letter to Evelyn Feldman Roth. December 17, 1933. Written from the Hotel Gramercy Park, New York City

Archives of Adler University, Chicago, IL, US. Donated by Dr. Penny Silvers.

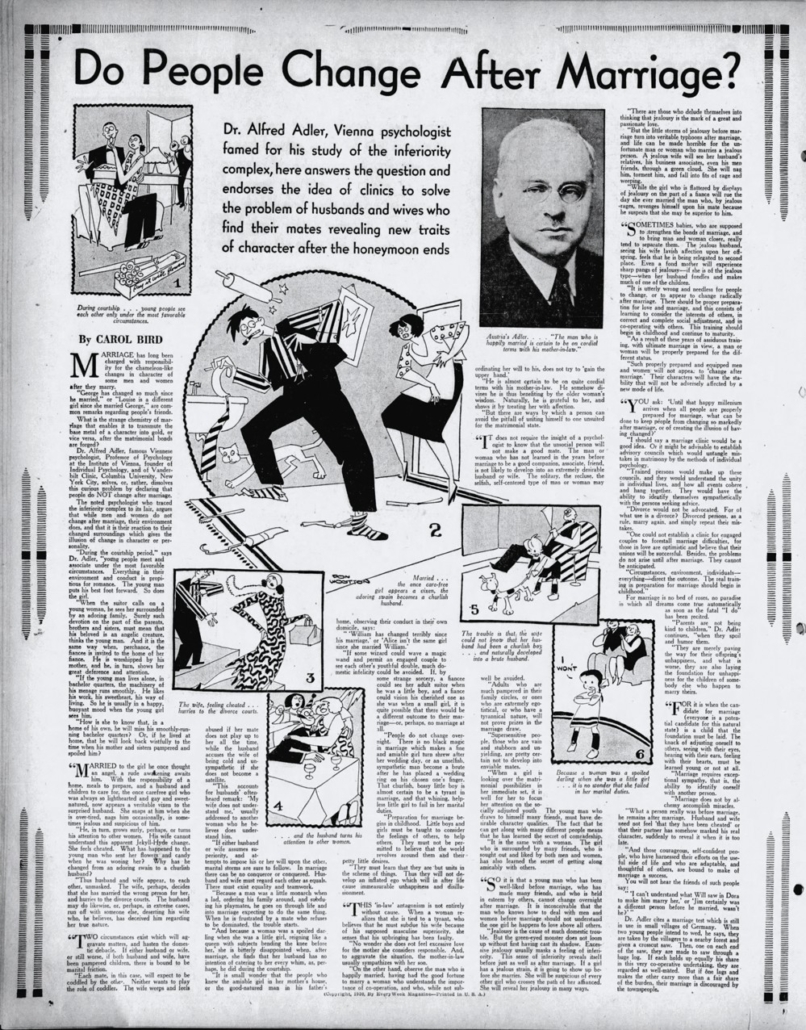

Newspaper Article “Do People Change After Marriage?” (1930)

An article discussing Adler’s views on love and marriage.

Southwest American, April 26, 1930, p. 18. www.ancestry.com

Adler in America

• 1926 – First American lecture tour. Venues included Community Church of New York, The New School for Social Research, Harvard University, and Columbia University. [1]

• 1928-30 – Lectured at the New School for Social Research (NYC) and became Visiting Professor at the Long Island College of Medicine (Columbia University Extension in NYC) and director of a Child-Guidance Clinic. [2]

• 1930 – Opened an Advisory Council of Individual Psychology clinic at the Community Church of New York. [2]

• 1932-34 – Professor at Long Island College of Medicine (Brooklyn, New York), Foundation of the Adler Medical Psychology Clinic (Brooklyn), also active at the New School for Social Research in Manhattan.

• 1934-35 – Permanent emigration to the U.S. amid rising threats in Austria. Alfred and Raissa took up residence at the Gramercy Park Hotel. The three adult children Alexandra (33), Kurt (30) and Nelly (25) followed to U.S. [3][4][5][10][11]

• April 1935 – Chicago: Launch of the International Journal of Individual Psychology (edited by Alfred & Alexandra Adler); this later evolved into today’s Journal of Individual Psychology (now published by University of Texas Press) [6][7][8]

• 1937 – Died in Aberdeen (Scotland/UK) while still actively lecturing internationally. [2]

Family

• Valentine Adler (1898–1942): Political activist and writer; remained in Europe and died under tragic circumstances in the Soviet Union. [2]

• Alexandra Adler (1901–2001): Became a well-known neurologist and psychiatrist in Boston, affiliated with Boston University. [2][9]

• Kurt A. Adler (1905–1997): Psychiatrist in New York; later leadership at the Alfred Adler Mental Hygiene Clinic and teaching at the Alfred Adler Institute (NY). [2]

• Cornelia “Nelly” Adler (1909–1983) later Stenberg (1932), finally Michel (1942): Actress/theatre educator including work at Bard College (NY) [10][11]

• Raissa Timofeyevna Epstein (1872–1962), a Russian-born intellectual and teacher; continued her involvement with the Adlerian movement in the United States and engaged in broader social and political activism. [2]

Facts about Adler in America

Library of Congress, Manuscript Division (Washington, D.C.)

“Alfred Adler Papers,” Manuscript Division (Washington, D.C.) — c. 9,300 items; 10.6 linear feet; 4 microfilm reels; 972 digital files. Contents include U.S. lectures and a 1937 letter from Albert Einstein discussing Freud vs. Adler. (The Einstein item is noted in the finding aid.) [12]

Standing among psychologists (quantitative ranking)

In the widely cited Haggbloom et al. (2002) study of “The 100 Most Eminent Psychologists of the 20th Century,” Adler ranks #67 [13][14]

Institutional legacy in North America

Adler University (Chicago & Vancouver), founded as Alfred Adler Institute of Chicago in 1952, and the North American Society of Adlerian Psychology (NASAP, founded 1952) continue his name and tradition; the Journal of Individual Psychology is now published by University of Texas Press. [8][15][16][17]

Alfred Adler — Key Works in English with brief summaries

• The Neurotic Character / The Neurotic Constitution (1912/1917, Eng.)

Early, more clinical account of neurosis as a style of life—goal-oriented (teleological) compensations for felt inferiority. [18]

• Study of Organ Inferiority and Its Psychical Compensation (1917, Nervous & Mental Disease Monograph No. 24; trans. Smith Ely Jelliffe)

Proposes that congenital or functional organ weaknesses spur psychological “compensations,” shaping character and vulnerability to neurosis—an early cornerstone of Individual Psychology.

• The Practice and Theory of Individual Psychology (1927, Engl. ed.)

Adler’s concise statement of Individual Psychology: lifestyle, goal-directed behavior, social interest, and birth-order as pillars of personality. [18]

• Understanding Human Nature (1927)

A highly readable overview of how early memories, family dynamics, and “fictional final goals” shape character and everyday problems. [19]

• The Science of Living (1930)

Applies Individual Psychology to real life—work, love, sex, marriage, and education—linking “inferiority feelings” and “striving for superiority” to social responsibility. [20]

• What Life Should Mean to You (1931)

Popular lectures turned book: practical guidance on courage, early memories, dreams, school influences, crime prevention, work, love, and community feeling. [21]

• Social Interest: A Challenge to Mankind (1938; from the 1933 German Der Sinn des Lebens)

Adler’s late synthesis: human flourishing depends on Gemeinschaftsgefühl (social interest)—cooperation over competition as psychology’s ethical core. [22]

• Posthumous English anthology: The Individual Psychology of Alfred Adler (1956, ed. H. L. & R. R. Ansbacher)

The most influential English compilation of Adler’s work organized Adler’s scattered papers into a coherent system. A permanent bestseller in its field until today. [18]

• Co-operation Between the Sexes: Writings on Women, Love and Marriage, Sexuality, and Its Disorders (1978; ed. & trans. H. L. & R. R. Ansbacher)

Curated essays on women, love, marriage, and sexuality that foreground Adler’s critique of Freudian determinism and his ideas on equality of the sexes and “masculine protest.”

Mode of Travel

• In 1926, the only practical way to cross the Atlantic from Europe to the United States was by ocean liner. Transatlantic steamship travel was safe, reliable, and relatively fast (typically took 7–10 days, depending on the ship and route).

• Mature steamship networks made travel safe, reliable, and scheduled

• The U.S. in the 1920s was hungry for new psychological theories, especially those applicable to education, child-rearing and love and marriage, which made Adler an ideal guest lecturer. Adler’s U.S. travels (1926 onwards) were part of a wider trend: Freud, Jung, and many others also toured America in the early 20th century.

[23] [24] [25][26]

List of sources

1 Bottome, Phyllis. Alfred Adler: A Biography. London: Faber & Faber, 1939. (Confirms the 1926–27 U.S. tour and venues incl. Community Church, New School, Harvard, Columbia.) https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.167738/2015.167738.Alfred-Adler-A-Biography_djvu.txt?utm_source=chatgpt.com

2 Library of Congress, Manuscript Division. “Alfred Adler Papers, 1885–2001.” Finding aid, rev. Feb 2024. (Authoritative timeline for 1928 New School course; 1929–30 Columbia Extension & child-guidance clinic; 1930 Community Church clinic; 1932 Long Island College of Medicine; 1937 death.) https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms009144.3

3 City of Vienna (Wien.gv.at). “The Life and Work of Alfred Adler.” (Official biographical overview.) https://www.wien.gv.at/english/history/commemoration/alfred-adler.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com

4 Adler University. “Alfred Adler History.” (Institutional legacy/context.) https://www.adler.edu/alfred-adler-history/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

5 Ramsey County Historical Society Review (Fall 2003). “Alfred Adler and his 1937 Lecture at the St. Paul Women’s City Club.” (Notes New York period and residence at Gramercy Park Hotel.) https://rchs.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/RCHS_Fall2003_Ballou.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

6 WorldCat record: International Journal of Individual Psychology (Chicago: International Publications), 1935–1937. (Editors: Alfred Adler; 1937 Alexandra Adler.) https://search.worldcat.org/title/International-journal-of-individual-psychology/oclc/1640276?utm_source=chatgpt.com

7 University of Akron Digital Collections. International Journal of Individual Psychology (issues, 1935–36). https://collections.uakron.edu/digital/collection/p15960coll25/id/14286/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

8 University of Texas Press. “The Journal of Individual Psychology.” (Current successor journal; published for NASAP.) https://utpress.utexas.edu/journals/journal-of-individual-psychology/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

9 Harvard Gazette. “Alexandra Adler, 99, was one of Harvard’s first women neurologists,” Jan. 18, 2001. (Family chronology & U.S. career of Alexandra.) https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2001/01/alexandra-adler-99-was-one-of-harvards-first-women-neurologists/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

10 biografiA: Lexikon österreichischer Frauen. Entry “Adler, Cornelia (Nelly).” (Cornelia’s U.S. theatre/teaching incl. Bard College.) https://biografia.sabiado.at/adler-cornelia/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

11 Library of Congress, Manuscript Division. “American Society of Adlerian Psychology Records.” Finding aid (founded 1951; renamed NASAP 1977). https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms009105.3

12 Internet Archive catalog record. What Life Should Mean to You (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1931). (First U.S. edition details.) https://archive.org/details/whatlifeshouldme0000adle?utm_source=chatgpt.com

13 Journal of Mental Science (Cambridge Core). Review notice for What Life Should Mean to You (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1932) — U.K. edition retitled What Life Could Mean to You.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-mental-science/article/what-life-should-mean-to-you-by-alfred-adler-edited-by-alan-porter-london-george-allen-unwin-ltd-1932-pp-300-price-10s-6d/A7CB3E0D8AF394232937E25DF33B3AE3?utm_source=chatgpt.com

14 Europeana Exhibition. “Departure and arrival.” (Typical 1920s transatlantic crossing times ~7–10 days.)

https://www.europeana.eu/en/exhibitions/leaving-europe/departure-and-arrival?utm_source=chatgpt.com

15 North American Society of Adlerian Psychology (NASAP). “About NASAP.” alfredadler.org. Established 1952; mission and scope. https://www.alfredadler.org/about-nasap

16 Library of Congress, Manuscript Division. American Society of Adlerian Psychology Records, 1951–1970. Finding aid (notes: founded 1951; renamed NASAP in 1977). https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms009105

17 Adler University. “Alfred Adler History.” Institutional history/legacy page. https://www.adler.edu/alfred-adler-history/

18 Adler, Alfred. The Individual Psychology of Alfred Adler: A Systematic Presentation in Selections from His Writings. Ed. & annot. Heinz L. Ansbacher, Rowena R. Ansbacher. New York: Basic Books, 1956. (WorldCat record.) https://search.worldcat.org/title/oclc/5692434

19 Adler, Alfred. Understanding Human Nature. Trans. from Menschenkenntnis. New York: Greenberg, 1927. (Internet Archive record of 1927 ed.) https://archive.org/details/understandinghum00adlerich

20 Adler, Alfred. The Science of Living. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1930. (Internet Archive record.) https://archive.org/details/scienceofliving029053mbp

— Modern reprint reference: Routledge/Taylor & Francis, “Psychology Revivals” edition. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9780203386750/science-living-psychology-revivals-alfred-adler

21 Adler, Alfred. What Life Should Mean to You. Ed. Alan Porter. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1931. (Internet Archive catalog record.) https://archive.org/details/whatlifeshouldme0000adle

— UK retitle: What Life Could Mean to You. London: Allen & Unwin, 1932. (Open Library record.) https://openlibrary.org/books/OL6764778M

22 Adler, Alfred. Social Interest: A Challenge to Mankind. Trans. John Linton & Richards Vaughn. London: Faber & Faber, 1938. (Digitized text with publication notes.) https://adler.institute/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/social-interest.pdf

23 Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Ship — Passenger liners in the 20th century.” Background on ocean-liner era and speed. https://www.britannica.com/technology/ship/Passenger-liners-in-the-20th-century

24 Europeana Exhibitions. “Departure and arrival” (Leaving Europe: A New Life in America). Notes typical steamship crossing time 7–10 days. https://www.europeana.eu/en/exhibitions/leaving-europe/departure-and-arrival

25 EBSCO Research Starters. “Transatlantic steamer service.” Overview of steamship era and reduced crossing times. https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/transatlantic-steamer-service

26 New York Public Library Blog. “Maury and the Menu: A Brief History of the Cunard Steamship Company.” 30 June 2011. https://www.nypl.org/blog/2011/06/30/maury-menu-brief-history-cunard-steamship-company

Bluvshtein, M. (2020). Individual Psychology as a “living force of progress.” Journal of Individual Psychology, 76(1), 6-20.

Ellenberger, H. F. (1970). The discovery of the unconscious: The history and evolution of dynamic psychiatry. Basic Books.

Hoffman, E. (1994). The drive for self: Alfred Adler and the founding of Individual Psychology. Addison-Wesley.

Orgler, H. (1963). Alfred Adler: The man and his work; Triumph over the inferiority complex. New American Library.